I made a big hoo-hah about starting this Substack with four in the bank, because I know how my life goes. I’m on my fifth week now and I’ve drained the bank, so I’m coming to you live and on the fly, which is how it’s probably mostly going to be, and how it’s probably best. A few weeks ago, though, in the usual phenomenal chaos, I accidentally ghosted my on-off therapist of 11 years, and am yet to deal with all the guilt and shame that has brought me, so I’m at risk of using this as my space for therapy. Oh well! You seem nice enough.

I’d love to talk to you about the experience of being in hospital with a small child in the UK in 2024 (the reason I needed to drain the bank). I’m going to keep the medical details loose, of course, but I’ll share what I need to tell the story. I think I probably want to say something here about how, yes, I do appreciate the concept of a national health service and I know it’s stretched beyond all imagining and I know it’s not the individuals’ faults. And I know it’s not working.

After a scary episode and a long period in A&E, Z (4) was admitted to a children’s ward for four nights. Just before we were admitted, the shift happened from “what are you doing here clogging up our services you stupid hysterical woman?” to “you awful neglectful mother, how could you let it get this bad?”. Towards the end, there was another more subtle shift to “we need to make sure she’ll be safe in your care before we can release her from this hopeless place (that you brought her to)”. Did Rihanna find love in an NHS children’s ward?

The issues were blood sugar related and Z was just beginning to recover from a particularly vicious vomiting bug. If you’ve had a vomiting bug before, or vomited, or been unwell in any way, or are a human being, you’ll know this can be a time of profound toast nibbling. There are occasional cravings for a Digestive biscuit or some salty crisps or a bit of pear. You may feel strong enough to sip a sugary drink.

Well, from the moment she stopped vomiting, after three straight days of vomiting water on a 20-40-minute loop, doctors and nurses were hounding me about whether she was eating “normally” yet. One of them sidled up to me to check in on food intake while we were paying a very brief visit to the courtyard of sadness, where Z tried valiantly to enjoy a Little Tikes Cozy Coupe. She wasn’t allowed in the playroom, because of contagion. Some good souls had brought her a Peppa Pig fantasyland to play with on the floor of her room.

The room was grim and prisony, with peeling blue floors and dismembered stickers of Ariel and Dora the Explorer on the forgotten walls. The toilet was next door, positioned just so that it was a Krypton Factor challenge maneuvering Z’s drip to the doorway. It smelled bad and had a shower so abject that I opted not to bother for the entire stay. We closed the door on it, but it was there. Z was expected to eat “normally” while sitting, cannulas in, drip attached, blood all over her hands, a metre from the toilet.

“Dinner’s ready!” they’d yell in the door and I’d approach the trolley on Z’s behalf. I’d try to be helpful, getting my tray and cutlery ready so I didn’t waste too much of anyone’s time, but I’d invariably get it wrong. You don’t need a tray for a sandwich, put it down. Get out of the way. Give me the tray, hurry up. You didn’t order chips. You ordered jelly but I only have orange juice. Slip slap slop.

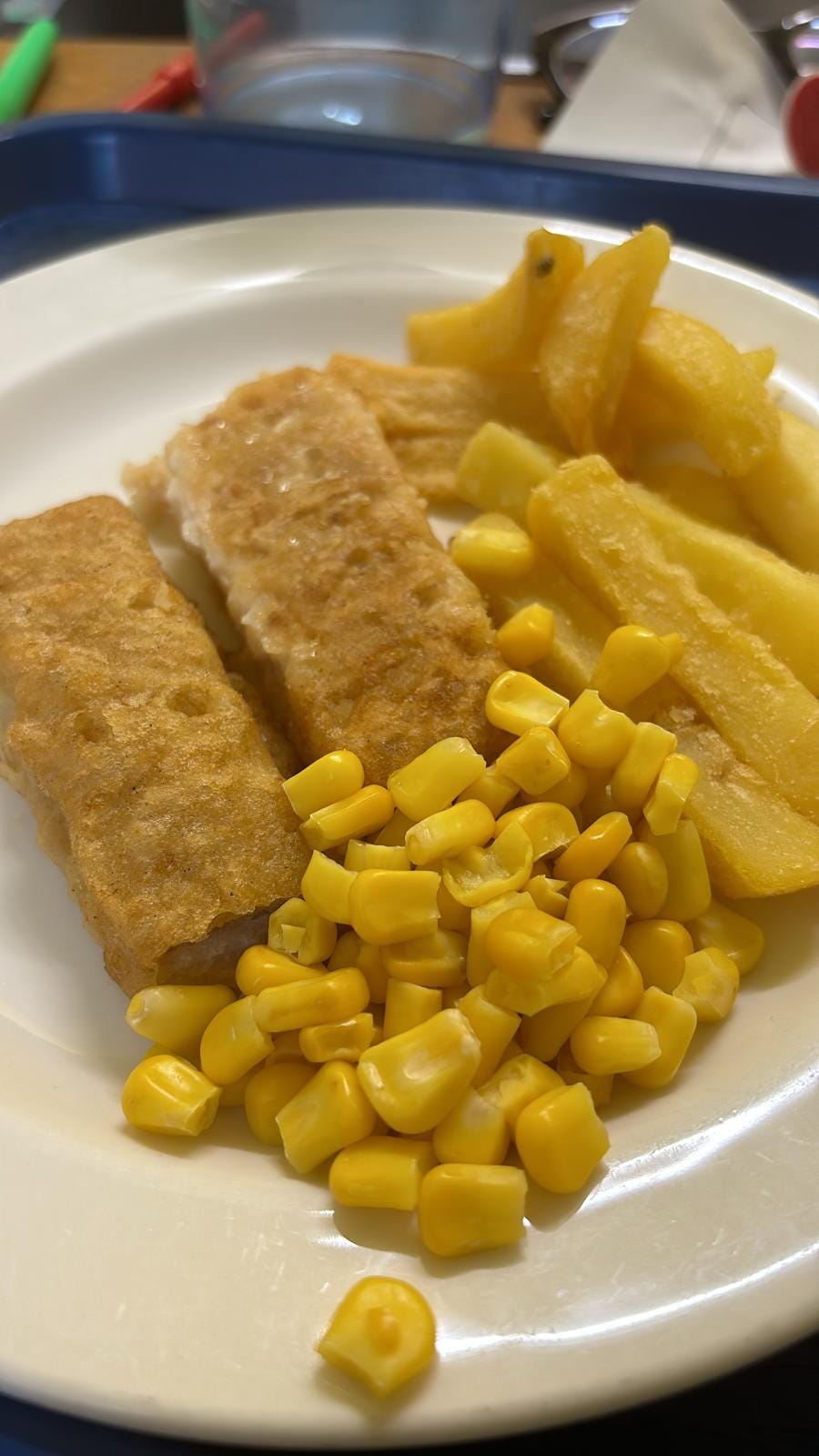

As a person, I prefer to eat things that are good, but I can quite easily find pleasure in average to bad food, like plane meals and school dinners. This was not food, though. This was a terrifying weirdness, blooped in and out of trays. I’d try to play it safe for Z so as not to make her nauseous, but the fish fingers were congealed, the chips pallid and hard, the macaroni cheese had an undissolved powder in it that wasn’t flour. Breakfast was thin white toast, cold in a metal box. Noone told you where to find it. The parents of the patients who had been in the longest passed along the secret location of the cold toast. There was some sugar-free jam.

“Is that all she’s eaten? Just a banana?”

People are in and out, doing obs, pricking tiny fingers, passing judgments, keeping secrets pertaining to my child’s body, the traffic never slows. The blood pressure cuff tightens and loosens. They assume I can tell the difference between them all, whether they’re doctors or nurses or food service assistants or plumbers or consultants, but of course I can’t. Are they here to check the shower head or the ingredients of my child’s blood?

We rarely see the same face twice. In they blunder. In and out of our cell. Jotting things down. Answering my many questions, but not. Never actually answering them at all. Behaving as though the patient is not a child. Looking at her cannulas and bloodied hands and telling her the next one won’t hurt, as though she doesn’t already know exactly how it feels. Furrowing their brow in sheer perplexity when she expresses an emotion. Telling her she can have a sticker from an ugly sheet, which one is her favourite? Is it the monster with one eye? Promising her she’ll be able to go home if she’ll just be quiet and let them stick more massive needles into her body whenever they want to. Just do this kid, and you’ll go home. And this. And this. And this. And this. And this. (Still here? You only have yourself to blame.)

I learned a lot about what our society thinks of children, the extent adults will go to to make them do what they want them to do in any given moment. I learned not very much at all about my child’s condition.

“WOMAN, WHAT IS WRONG WITH YOU? WHY CAN’T YOU RETURN YOUR TRAY?”

It’s less than an hour after I’ve located the cold toast box and someone swings in, yelling. “Oh”, she says, “it’s toast. I thought it was last night’s pizza”. I am agog, but that’s just my standard state now. I say, surprising myself, almost in a trance, “I think I’m just going to wait until you apologise for shouting at me”.

The consultant comes once a day in the morning. I tell her how tired I am of people telling my child to eat. At home, I trust my kids to know their own bodies, when they’re hungry and when they’re full, and this is everything I hate, playing out in front of me while my child is most vulnerable. I cannot stand it.

“Just do what you’d normally do at home then!”, the consultant says.

Boil an egg? Get some nice bread? Make her favourite pasta? Chicken soup with lokshen? I can’t. Of course I can’t. I start ordering only tuna sandwiches from the trolley. Later, I Deliveroo two X Happy Meals in a row and Z demolishes them, but I am worried and sad about what these meals will mean for her now, in the real world, how unhappy they might be.

I nearly pass out watching the third cannula go in, and Z is unbothered, which breaks my heart. I eat half of an M&S egg mayo sandwich, something I’ve never knowingly not finished. There’s no slop for parents.

I sob with sheer frustration and overwhelm on the corridor floor so I don’t have to do it in front of Z. A kind, young nurse takes me for a walk, but she doesn’t know any more about what’s going on than I do. I take Z to M&S to do a supermarket sweep. As she chucks pretzels, croissants, pineapple chunks in the basket, she asks, “is this stressing you out?”, exposing how well I have regulated my emotions this week.

Back in bed prison, Z gets out the cheese puffs. People in, people out. The beeping, the beeping, the beeping. The babies crying MAMA, thoughts of the baby I haven’t seen all week at home. Z isn’t eating her cheese puffs and I feel the panic surging – they’ve got to me. Someone will be in soon suggesting I force feed her mince instead. Z hands me the cheese puffs. “They don’t taste normal”. Of course they don’t taste normal! This isn’t a normal situation! How could anyone eat NORMALLY in … the packet catches my eye. REDUCED FAT, it says, a little too small. I laugh, a little too hard. Then we get to go home.

So much sympathy. I’ve done plenty of stints on the children’s ward (daughter has severe asthma) and it’s always dreadful. I’ve seen some harrowing things and some shocking things and one quite funny thing (4 teenage girls admitted because they’d eaten mushrooms they found on the school playing field and hoped they’d get high - they didn’t they got sick. They were fine but their parents were fuming.)

It’s so bad that whenever I am having a shitty day, pausing to remind myself that at least I’m not on the children’s ward with a wheezing child will always make me feel better.

I’m glad you got to go home. I hope Z is on the mend

The particularly telling detail about the three phases of response - 'why are you clogging up the A & E unnecessarily/'; Why did you wait so long?' and ' Flagging up social services' was recogniseable in my time with my 3 year old with a vomiting bug.